Naoki Urasawa

Interview by David Cirone

January 25, 2019

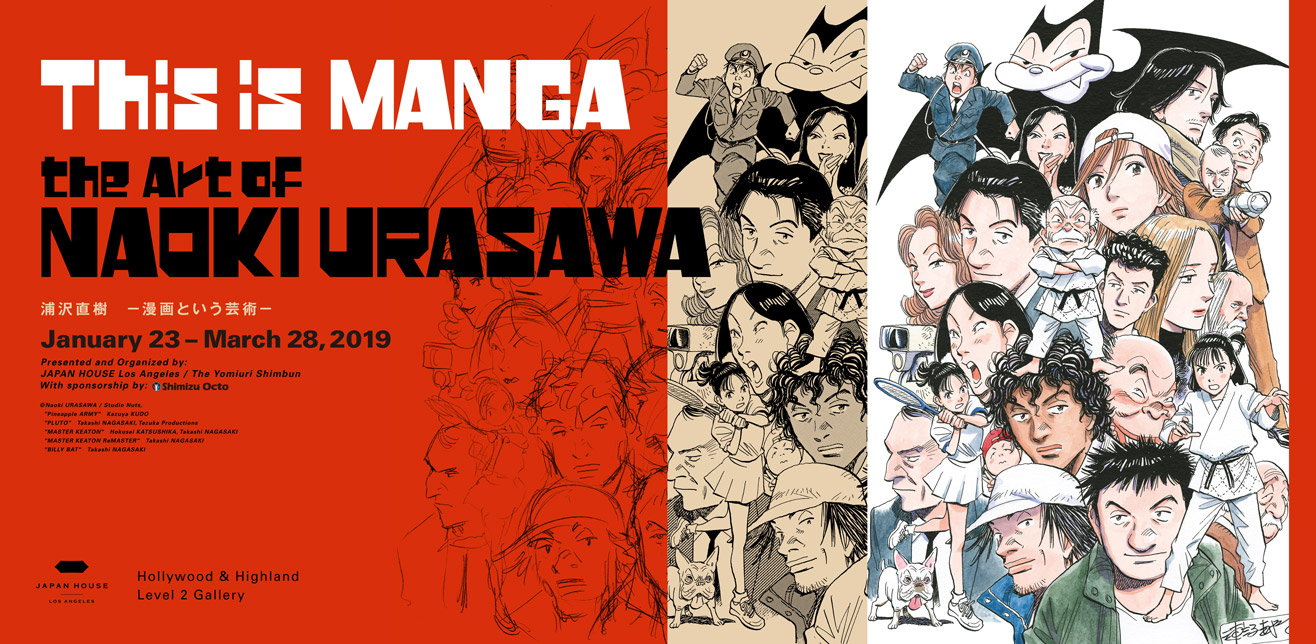

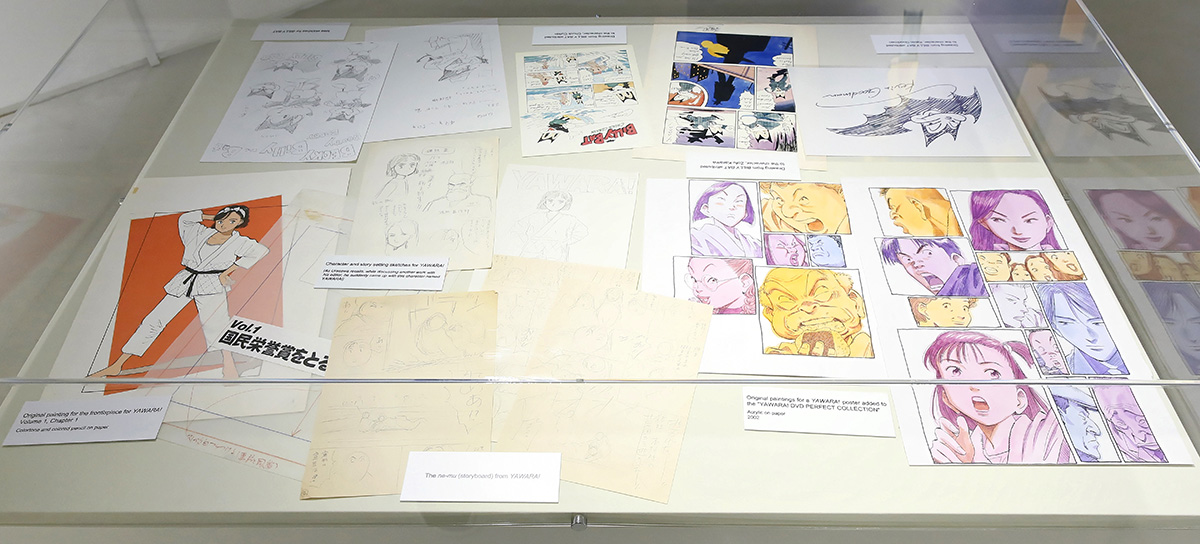

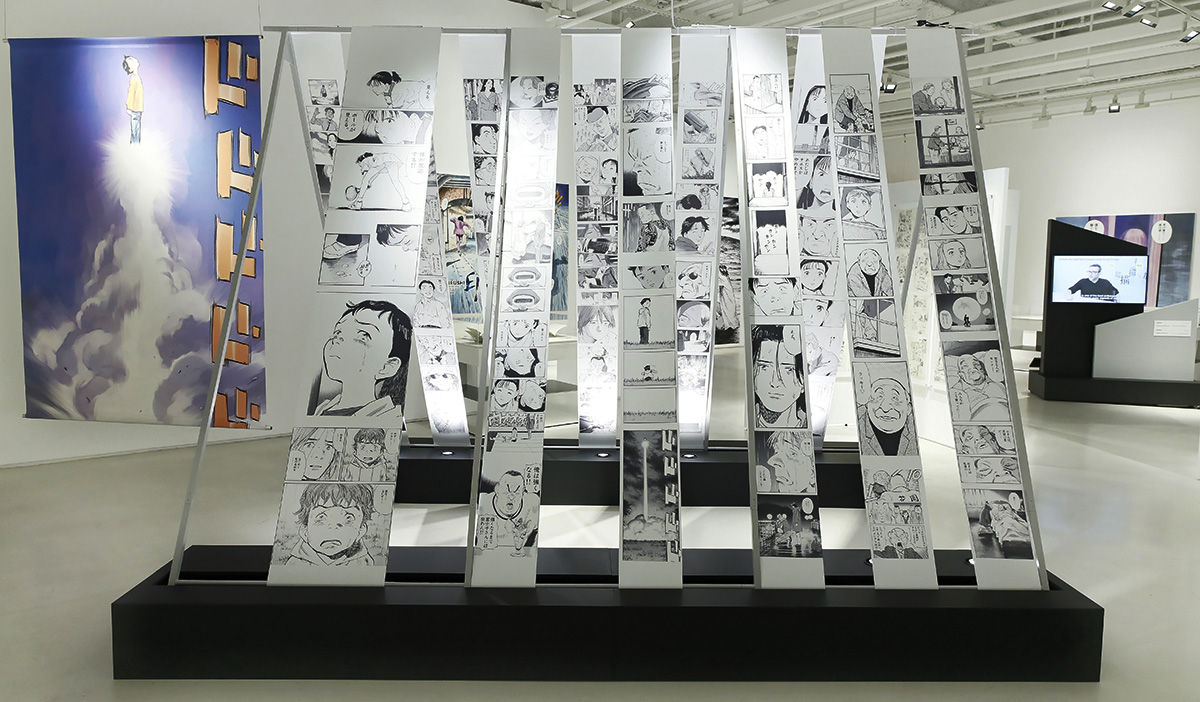

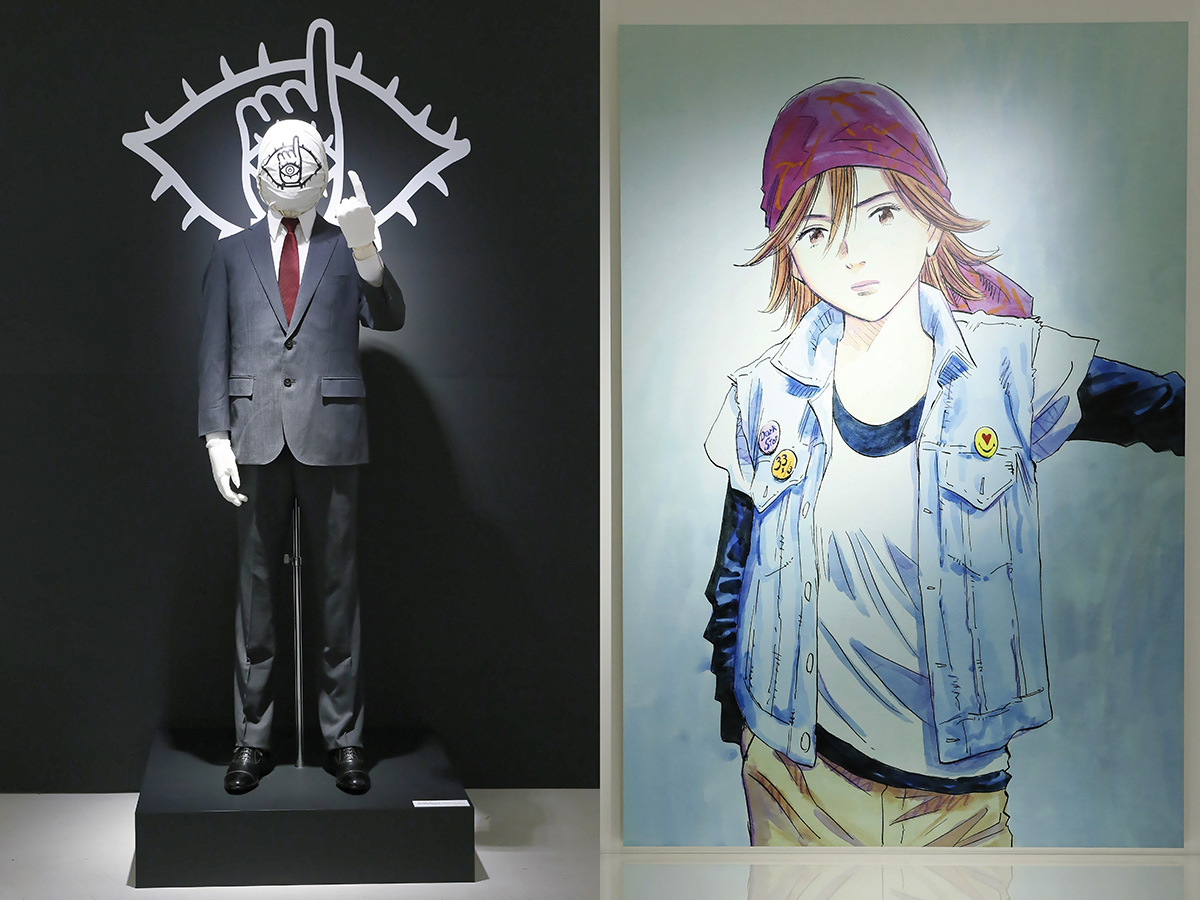

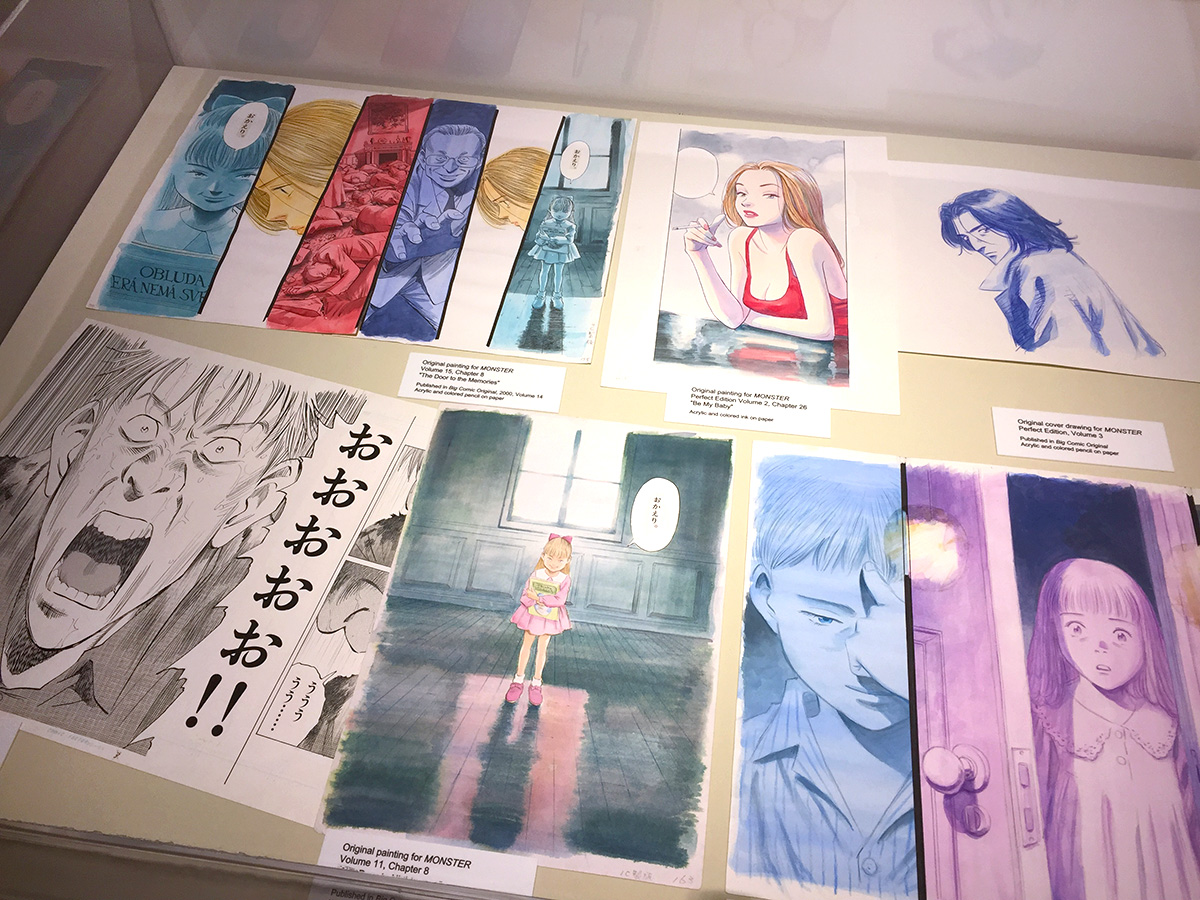

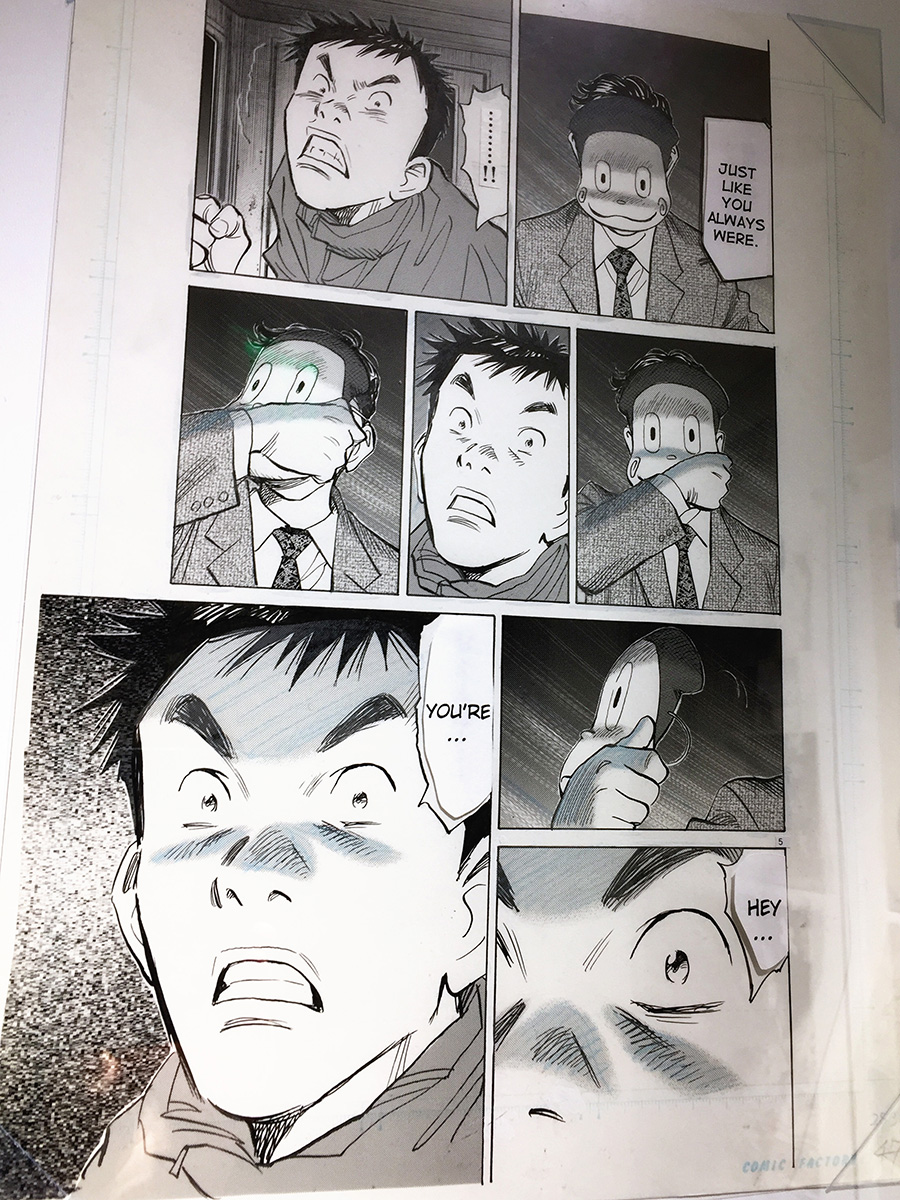

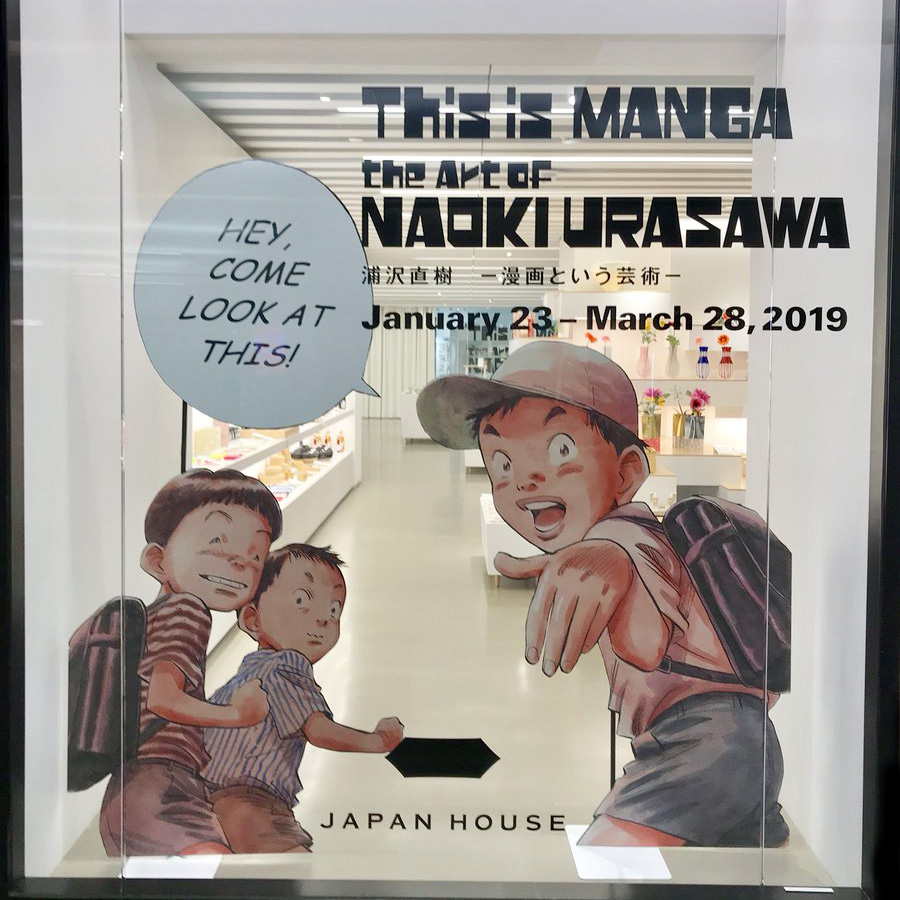

We sat down for a one-on-one interview with famed manga creator Naoki Urasawa at the opening of his first North American art exhibition, “This is MANGA – the Art of NAOKI URASAWA”, which runs January 23 – March 28, 2019, at JAPAN HOUSE Los Angeles. The multi-media exhibition, which includes more than 400 pieces of original artwork, storyboards, paintings, and sketches, is a comprehensive and in some cases giant-sized retrospective of Urasawa’s artistry, which has led to over 127 million sales of his work in Japan alone and built a devoted worldwide fan base.

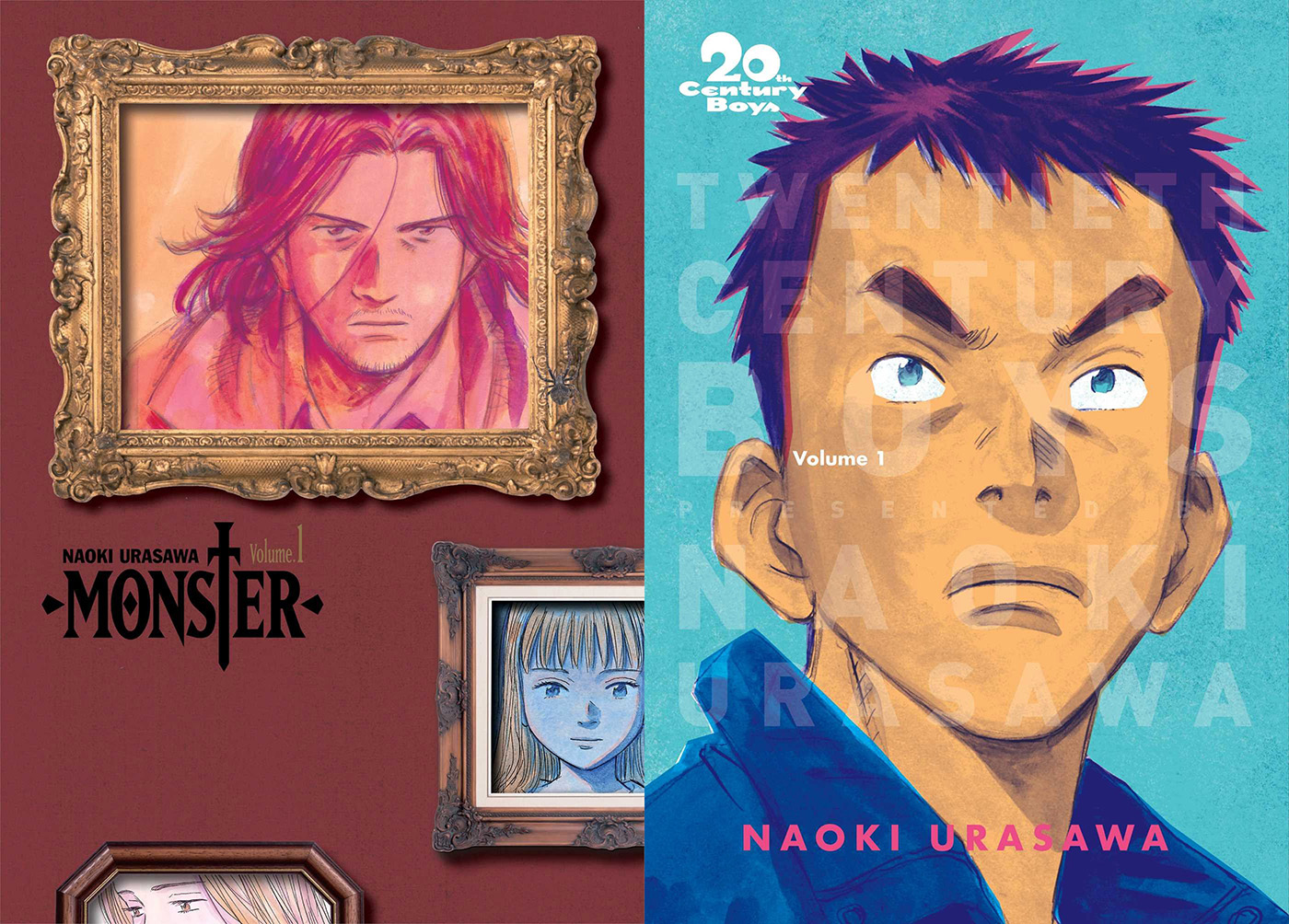

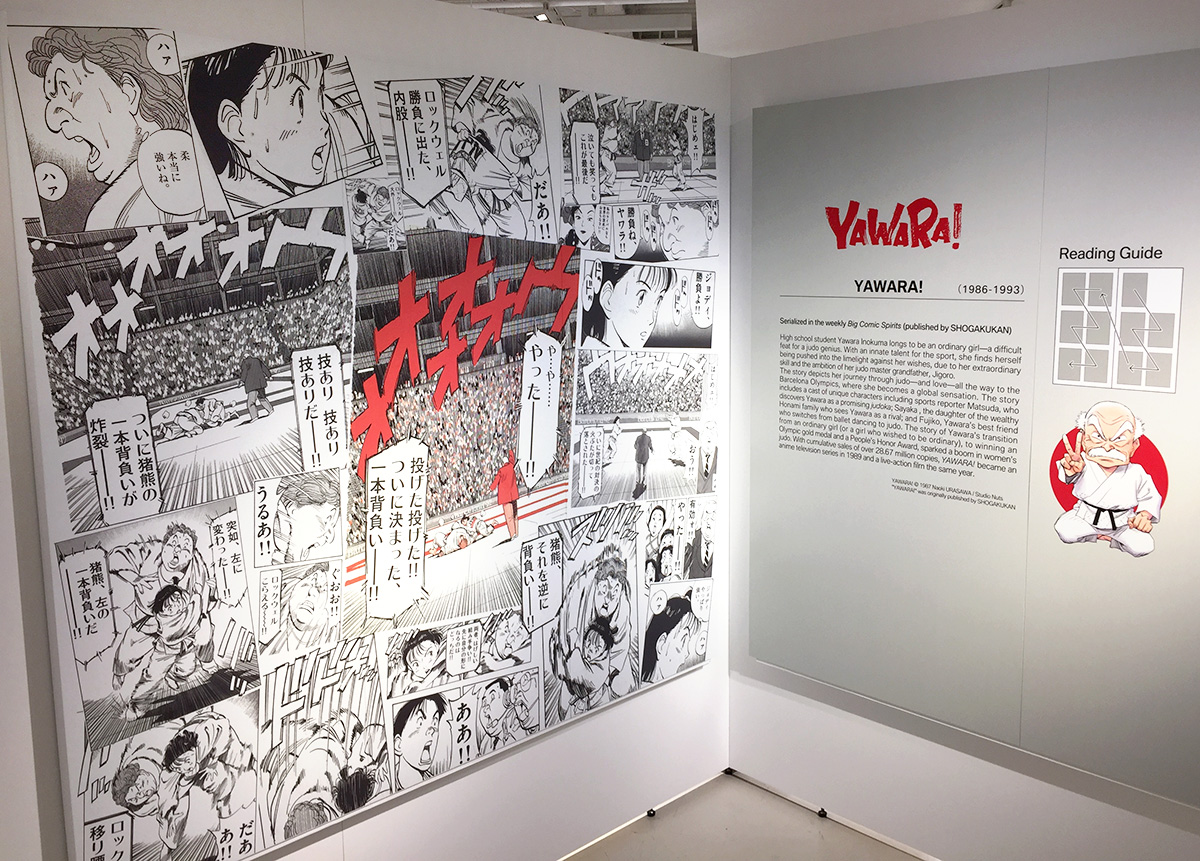

Surrounded by the climactic scene from the psychological thriller Monster, a life-size mannequin of the fearsome “Friend” from science-fiction mystery 20th Century Boys, and a colorful splash page from the beloved judo manga Yawara!, we talked about Urasawa’s inspirations, techniques, and the real-world event that shaped an iconic chapter of one of his most celebrated works. (Warning: minor spoilers ahead for Monster and 20th Century Boys)

Congratulations on your first exhibition in America.

Urasawa: Thank you.

My own experience with your work began with Monster, and like many of your readers, I was hooked by the unique look of your characters’ faces. What qualities do you focus on when you’re illustrating your characters?

Urasawa: When someone mentions the world “manga”, I think the first impression most people have is like what they think when they see the “smiley-face” on the Nirvana T-shirt you’re wearing. They think it’s just a very simple form of expression, just a simple abstract of someone’s emotions. But in the case of real humans, I think that’s completely erroneous. There are no identical faces in different situations, but instead there are subtle changes that occur in a person’s facial expression from moment to moment, and that’s what I try to capture. One time, I gave a lecture at a university, and it was an arts-focused institution, and I told the students, “If you really want to understand how to create manga, you shouldn’t go to art school first — you should take drama classes first and learn to understand human emotions and expressions before trying to step into the world of manga.”

There’s a strong cinematic quality in your visual style. When you’re planning a scene, do you think like a film director? Do you consider wide shots, closeups, angles?

Urasawa: I think that way I approach manga would be close to storyboarding a movie, and I’ve been approached a few times with offers to direct films. But when you get into the world of movie-making, so many restraints come with that, so many variables that you can’t control anymore, like the budget for example, or the casting of the actors and the schedule might be out of your hands. There are a lot more people that get involved. With manga… as long as I have a pen and paper, I can create something new. I can begin to work in my own form of expression without limitations. And that fast turnaround makes creating manga preferable to me over doing movies.

What are the elements that influence how you structure a page? How do you decide when to condense a sequence into many panels, and when to expand a moment to a full page for visual impact?

Urasawa: I’ve been drawing manga since I was 4 years old, so I’ve been doing this for over 50 years now. I don’t think about visual pacing very much — for me, it’s like breathing. I just follow the inspiration naturally as it comes. When I start to structure a story narratively, the question of tempo — developing a character moment-to-moment and then jumping to a two-page spread — how do you determine where that happens? It’s like breathing to me — I know when it feels right. I know when I feel like, “Now I need something,” so I develop the pages naturally as they come.

When you’re planning an extended storyline like Monster or 20th Century Boys, how many story details are decided in advance before you start a new series? How much room is there for inspiration or new directions after you get started?

Urasawa: When I start a new project, I start with the larger arc of the story. I visualize a movie trailer for that story, and after I compose this movie trailer in my mind, there comes a point where I’m so excited about it that I have to write the story. And then I imagine, “Where do I start to begin to tell this narrative?” and that’s usually the first chapter. Once this process starts, the story tells me where it wants to go next. I think if I tried to design a manga with each detail of the story planned out from the beginning, or tried to deliver a story where everything happens according to plan, there’s no way I could create something that would last five to seven years. Every time the story pulls me in a new or unexpected direction, even I’m surprised. If the story of the manga doesn’t keep surprising me, I wouldn’t be able to continue making it. There might be a scene I envision as I begin the project, something from that trailer I’ve visualized, but that scene might show up five years later as I’m illustrating the manga.

As you mention that, I think of the beginning of 20th Century Boys when Kanna pulls away the curtain and sees the robot. That’s in the very first chapter, but the narrative of the story doesn’t reach that scene until over 200 chapters later.

Urasawa: I remember when I first visualized that scene in the trailer format, and I put the scene in the very beginning of the story arc. Incidentally, when I was working on that scene, I could hear a baby crying in the konbini next store, and at the time I didn’t realize that Kanna and that baby were the same person. I just knew had to put that scene in the manga, and then later I surprised myself when I realized they were connected as the same person. After I illustrated the baby a few times, it hit me — “Oh, that’s her, she’s the one!” And I was just as surprised as the readers must have been.

During the exhibition preview, you mentioned that 9/11 affected the events of 20th Century Boys.

Urasawa: It was just a few weeks before the events of 9/11, and I had just delivered the manuscript for a chapter where these two giant robots fight and level all the tall buildings of Shinjuku. When I saw the real-life tragedy of that event in New York, I didn’t have the heart to illustrate that scene any more. So instead, I delivered nearly a whole chapter of Kenji just singing his song. At the time, I’m sure it was unheard of in a manga story, but I wanted Kenji to express how I felt at that moment.

Monster has over 160 chapters, 20th Century Boys and 21st Century Boys have over 260 chapters combined. Why do you trust readers to be so patient and stay with your story for so long?

Urasawa: To be honest, I’m not thinking about the readers too much as I’m creating. I just try to tell a story that I find interesting myself, and as a result, if I stay interested and if I’m having fun, the reader reaction will hopefully follow along.

Which character have you created that’s closest to your own personality?

Urasawa: That’s a tough question — I’m not sure. If I’ve done that, it wouldn’t be one of the main characters. It would be someone on the sidelines.

Some readers might think you’re close to Kenji from 20th Century Boys, that your feelings about music are expressed through him.

Urasawa: If there’s a part of me in Kenji, you might see that in the older version, when he’s seen a few more things in life. I think I’m more on the cynical side.

Your stories have a strong theme of human interconnectivity. Relationships from the past and random meetings have unexpected effects on your characters. Why is this such a strong component in your storytelling?

Urasawa: I recently saw the Clint Eastwood film 15:17 to Paris. It’s based on a true story about three American soldiers who board a train to Paris and stop a terrorist attack. I feel that the style of character development and storytelling in that film is similar to my own. If you trace the history of those men, of all the things that happened to create the situation where they would be on that train together at that moment… I don’t know if “fate” is the right word, but the way it was depicted in the film… tracing back even further to their childhood where they were called into the school office together by a strict teacher. That’s how they meet, and years later, when they all decide to board this train together, they have the specific abilities they needed to stop the terrorist. Seeing all those elements come together, I feel like that style of storytelling is close to what you’re describing. I think world history is an even larger combination of these kinds of elements.

As a storyteller, would you say you’re most interested in finding a key dramatic event and then working backward to see how those characters got there?

Urasawa: In the case of 20th Century Boys, I was listening to some speech on television from someone at the United Nations, and in that speech, I just happened to hear a part where he said, “Without them, we would not have been able to reach the 21st Century…” And then I started thinking, “Who’s ‘them’? Who are those people?” And this happened when I was taking a bath, so I had to write that idea down as soon as I could.

You just began your new manga series Asadora! With so many respected series in your past, what new challenges have you set for yourself with this series?

Urasawa: The main character is a simple, normal woman who we don’t know much about, and to successfully capture her daily life and express it through a manga to find out how she got to where she is today is the biggest challenge for me right now.

Today we live in a new age of visual storytelling. American comics are more popular as collected editions instead of single issues, and even TV series are released as full seasons all at once. What’s special about publishing a story at the slower week-to-week or month-to-month pace?

Urasawa: When I was younger, the Steve McQueen movie The Great Escape was broadcast in Japan and –this is kind of unthinkable now – they separated the story into two parts. Part 1 ends as he starts digging and says, “To be continued.” So during the whole week before Part 2, of course my brain’s racing… “What’s going to happen?” “What are these characters going to do?” A colleague of mine, Mitani Kouki, he’s a playwright and screenwriter and he grew up in the same era as I did, and he had the same experience. When he saw that on TV, he was thinking the whole time about what could happen. And I think that separation, that gap between episodes, is a chance for the story to grow. You’re thinking about the story, about which directions the events could go to, about how the characters might split, about all the different possibilities of how to conclude the story. To me, if you consume media the way we do with modern trends – even I watch The Walking Dead quickly, thinking “next episode, next episode” – it doesn’t give the viewer time to think about where the story could go. You’re just fed narratives one after the other. And I think that a week between chapters in a manga is a good thing. It’s a way to step back and consider what you’re reading, and it has a stronger effect.

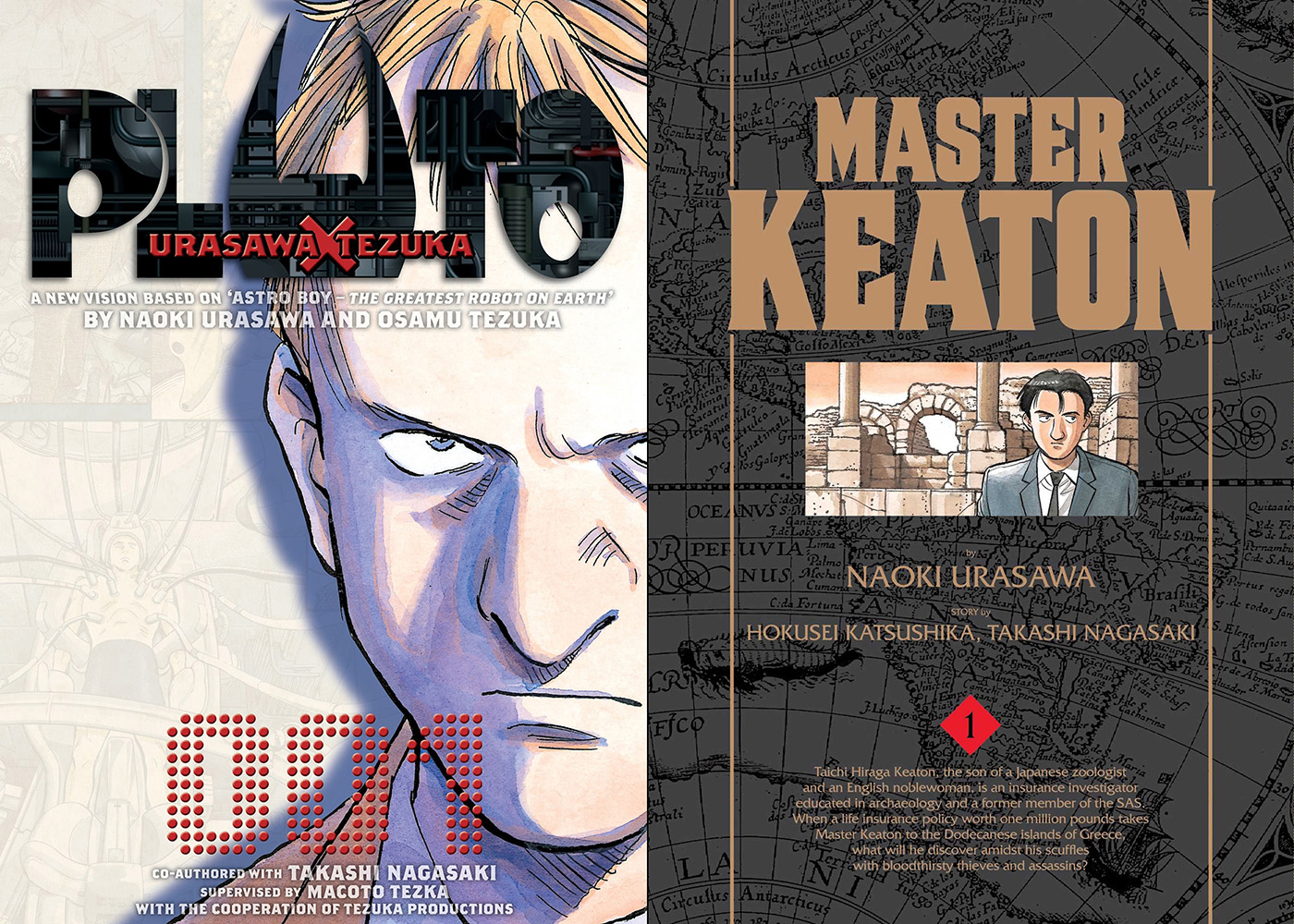

Your manga Pluto is an adaptation of one of Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy stories. In the future, a young manga artist is going to approach you with a similar request. What advice do you have for that young man or woman?

Urasawa: Don’t do it! That’s my advice. (laughs) You might be wondering why I say that. When I did Pluto, I really understood the gravity of what I was about to undertake, especially adapting a work by a master such as Tezuka. Having been under that pressure and having undergone such intense struggle, my advice to a young artist would be to not do it. The more pressure you feel, the more serious things become, and it could even lead to a health issue. I think for the sake of your own sanity, you have to stay away from that.

But if the artist is brave enough to approach you, chances are they won’t listen to you.

Urasawa: You’re right!

After its stop at JAPAN HOUSE Los Angeles from January 23 to March 28, “This is MANGA – the Art of NAOKI URASAWA” will continue to the JAPAN HOUSE galleries in London and Sao Paolo, continuing JAPAN HOUSE’s mission to foster awareness and appreciation for Japan around the world by showcasing the very best of Japanese art, design, gastronomy, innovation, technology, and more.

Exhibition Information:

https://www.japanhouse.jp/losangeles/exhibition/this-is-manga-the-art-of-naoki-urasawa.html

Presented and Organized by: JAPAN HOUSE Los Angeles / The Yomiuri Shimbun

Sponsored by: Shimizu Octo

In cooperation with: N WOOD STUDIO / SHOGAKUKAN / KODANSHA / POMATO PRO. / Yamato Global Logistics Japan / ANA / Bay Bridge Studio / AGASUS / VIZ Media

Special assistance provided by: Takashi Nagasaki / Kazuya Kudo / Hokusei Katsushika / Tezuka Productions Co. / Fujio Productions

Art Direction by: Kaitaro Kiuchi (POMATO PRO.)

Curatorial support provided by: Stéphane Beaujean (Art Director of the Angoulême International Comics Festival)

Naoki Urasawa Twitter: https://twitter.com/urasawa_naoki

Naoki Urasawa’s Music on Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/artist/4kmbC7n35u81LaR7VKyaaX

Japan House Los Angeles Information & Events: https://www.japanhouse.jp/losangeles

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/japanhousela

Twitter: https://twitter.com/JHLosAngeles

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/JapanHouseLA